Finished in 2025

There are 23 items here.

There are 23 items here.

A welcome recommendation on Threads and a lucky find on my first trip to the foreign-books specialized Kinokuniya in Shinjuku. What a long-reverberating delight it was to have this book in my backpack for two months, crawling through it at restaurants and cafes in Aoyama and Jinbōchō after dropping my son at summer science school, on a Tōhoku road trip, and around Kanamachi. The volume of notes I took, and the genealogy dive I went on, should be testament to it.

The Indo-European language family enjoys the dubious honour of being the one on which historical linguists cut their teeth. Later, they took the skills they honed there and applied them to other language families. Indo-European is consequently the best documented and in many ways the best understood of all the world’s language families, but it also drags the most outdated intellectual baggage behind it. It’s like the star patient of a tail-coated nineteenth-century doctor, hauled out woozily for public display, underwear slipping off its shoulder, fêted and abused in equal measure.

Historical linguistics probes the history that languages carry within themselves; archaeology tracks ideas and knowledge, the ingredients of culture; genetics tracks people.

I’ve been meaning to read some KSR since college, when my roommate recommended the Mars trilogy. It took reading his Wolfe- and Proust-adjacent A Story to get me to pick a novel of his and go for it.

I sure do appreciate a story grounded in a scientific understanding of how things actually work. It was a gravely curious exercise to compare KSR’s 2020s Earth, deteriorating on account of climate change, to ours, deteriorating on account of pandemic and social fabric rot. Ultimately I was mortified by what appears to be an argument that “If we are gonna get anything done, first some activists are gonna have to go systematically assassinate the 1,000 worst capitalists.” And everything in the book about expecting people to see a better system and just happily adopt it because it’s obviously better, especially the bit where the population of Earth switches away from existing social media to a Mastodon-alike because it’s “free and open”, gave me Gell-Mann nervousness about the rest of the book that I don’t have intimate professional knowledge of.

Ultimately, I appreciate the utility of a novel that attempts to present a credible account of how the world may end up in the near future, to motivate people to take some part in shaping how it does actually end up.

This was our entry into bringing kids to stage shows in Japan. Rey and I traversed Tokyo together to the majestic New National Theater and saw this, Obachetta, a colorful and mostly wordless dance performance on the theme of his beloved obake: countless folkloric Japanese ghosts and monsters. The show was entertaining, Rey was riveted, and I was thrilled by the stack of artsy flyers for other stage shows in Tokyo, hefty with promise that this is an entire scene, an entire lifestyle, that we can enter into as a family.

I think my soul treats classic dungeon-crawling aesthetics as a necessary nutrient, especially in the autumn and wintertime. Over the years I have gotten my intake from TTRPG sourcebooks, Etrian Odyssey, Dwarf Fortress, and other such supplements. This is a welcome addition to the diet, delivered on a substrate of wholesome manga heart.

I’ll forever treasure the ritual of gasping at a passage (usually encountered at the Katsushika Central Public Library while waiting for my kids to finish some activity in the neighborhood) pulling out my phone, capturing it with Apple’s OCR, then pasting it into Ulysses and into my iMessage thread with Sben, to kick off a little discussion about it.

This is also the first volume I intentionally read in multiple translations at once, depending on the situation: the Penguin Grieve when I had the library book handy, and the Yale Carter on the Kobo otherwise.

The dogs bark, the caravan moves on Arab proverb

This was a fine part of my grand TTRPG system hunt of 2025. I appreciate its fresh, modern, digital-first presentation and its breaking free from the D&D-rooted conventions that most games are still rooted in. I thought this might be a good system to run for my kid, but it’s a bit too high-concept and geared toward improv-ready grown-ups, versus Ryuutama which I ended up choosing instead.

(P.S. — This is the first Picocosmographia entry I’ve written using my new AI-assisted process. It reads my OmniFocus queue of books to write about, creates Hugo drafts with correct metadata, and selects a random one for me to write about.)

Before the show I met a fellow chilling by the drink machines on the waterside in Kitanomaru park, wearing a Rovo shirt, and got to talking for upwards of two hours. It turned out we’d both seen Rovo open for Clammbon at Liquid Room in 2002. He had encyclopedic knowledge of prog and classic rock, and had traveled to Europe and America numerous times to see some of my favorite bands. He clued me in to a Les Claypool appearance coming up at the Blue Note Tokyo in November.

I had sprung for the highest tier of ticket, guessing that this might be my last chance to see a semi-official King Crimson performance. I’m still working on inhabiting the right state of mind when at a concert, rather than just letting my mind wander in the default mode network. But I arrived at a pretty good meditative state of contemplating the accomplishment of such an extraordinarily low-entropy state. And generally recognizing that these musicians gave me a glimpse of the Eternal when I was particularly receptive to it as a teenager.

When I got very into the band Clammbon, my wife’s sister immediately recognized where their name had come from: this short story which is commonly read in grade school. It’s apparently commonly assigned in order to get children thinking about what ambiguous elements in a story might refer to, and each person develops their own idea of what the mysterious figure “Clammbon” mentioned in the beginning of the story might be.

I always meant to read the story myself, and found a collection on the shelf at the Katsushika Central Library, where I spend a lot of time these days waiting for my own children to do various activities about town. It didn’t make an especial impression on me, and I think I still have some study to do about its possible meanings, but I’m glad I finally traced the name of my beloved band back to its origin.

My read-through of the five novels in this Library of America volume continues. A few images and moments certainly grabbed hold of me and put me in a pretty particular 1978 SF state of mind. Other moments felt like too bare an exposure of the author’s own opinions about how societies ought to work; Always Coming Home seemed to me to be a more thorough and nuanced realization of a similar aim.

Luz Marina Falco Cooper sat in the deep window seat, her knees drawn up to her chin. Sometimes she gazed out through the thick, greenish glass of the window at the sea and the rain and the clouds. Sometimes she looked down at the book that lay open beside her, and read a few lines. Then she sighed and looked out the window again. The book was not interesting. It was too bad. She had had high hopes of it. She had never read a book before. She had learned to read and write, of course, being the daughter of a Boss. Besides memorizing lessons aloud, she had copied out moral precepts, and could write a letter offering or declining an invitation, with a fancy scrollwork frame, and the salutation and signature written particularly large and stiff. But at school they used slates and the copybooks which the schoolmistresses wrote out by hand. She had never touched a book. Books were too precious to be used in school; there were only a few dozen of them in the world. They were kept in the Archives. But, coming into the hall this afternoon, she had seen lying on the low table a little brown box; she had lifted the lid to see what was in it, and it was full of words. Neat, tiny words, all the letters alike, what patience to make them all the same size like that! A book—a real book, from Earth. Her father must have left it there.

“Sasha’s house is down there,” said the variegated child, pointing down a muddy, overgrown lane, and sidled away so effectively that he seemed simply to become part of the general mist and mud.

This has continued to be the representative heartwarming slice of life manga of recent years. Every line is gently rounded, every corner softened — both in the art and in the story.

The bit with Weinzel and Palsuet meeting Mrs. Cyan stands out as one of my favorite episodes of all of FSS: character drama that also enriches the history and culture of the Joker Star Cluster. As is my new method, I skimmed over a bunch of the standing around in nondescript outdoor environments yelling about military campaigns.

Dawkins is of course the author who kicked off my adult nonfiction reading habit, and I’ll always read his new book when it comes out. I don’t know how many more times that will happen, if any. But I found “a sense of wonder” in his explication of how the immortal gene works, stumbling into the invention of such a vast and strange array of organisms along the way.

Sir D’Arcy Thompson (1860–1948), that immensely learned zoologist, classicist, and mathematician, made a remark that seems trite, even tautological, but it actually provokes thought. ‘Everything is the way it is because it got that way.’

The primatologist Richard Wrangham has promoted the intriguing hypothesis that the invention of cooking was the key to human uniqueness and human success. He makes a persuasive case that our reduced jaws, teeth, and guts are ill-suited to either a carnivorous or a herbivorous diet unless a substantial proportion of our food is cooked. Cooking enables us to get energy from foods more quickly and efficiently. For Wrangham it was cooking that led to the dramatic evolutionary enlargement of the human brain, the brain being by far the most energy-hungry of our organs. If he’s right, it’s a nice example of how a cultural change (the taming of fire) can have evolutionary consequences (the shrinking of jaws and teeth).

I’d been curious about reading Proust for about a decade: I gave him the tentative research treatment in bookstores where I examined the editions they had, practiced on CDs in the 1990s when you couldn’t know much about an album except what you could glean from the packaging. I read De Botton’s How Proust Can Change Your Life and then didn’t read Proust for eight years thereafter. I read the Atlantic article about reading Proust on one’s phone. I stood in a Brooklyn bookstore on a work trip and seriously considered picking up the shiny red Swann’s Way there, but had to admit I couldn’t be sure I’d really read through it, let alone the rest of the volumes.

Upon moving to Tokyo, the Katsushika Central Library became one of my favorite places. We visited nearly every day in the course of bringing the kids to Kumon, Shichidashiki, or other activities. On the shelf in the quite decent English section I found two volumes of the Penguin Proust, translated by seven different people, and learned that two more were in the stacks. All of my prior research and concern about getting just the right translation and the right format were replaced by the notion of how meaningful it would be to start reading Swann’s Way any time I was in the library, and only when I was in the library. It could be something to look forward to, something to add beyond my regular reading pile, and something to progress slowly without worrying about how long it took to finish.

I lasted for a few weeks of only reading it when physically present in the library building, but eventually had to admit that I was captivated enough to want to borrow it for an overnight stay at my in-laws’. Not long after, I also got ahold of the ebook edition so that I could continue reading at any time.

There are some mysterious items on my OmniFocus project “Books to Read v9”. Usually I try to capture where I got a recommendation and why it stuck enough for me to record it. This one was just there, and when I looked at it I got a vague sense that whoever had recommended it had made it sound meditative and nourishing.

On a rare visit to California for work, I discovered the utopian Kepler’s Books, which felt like it belonged in a hip urban center, not a dismal walk down the unwalkable American street from my suburban hotel. There I spent an agonizing amount of time wandering from section to section, squinting at every recommendation card, trying to look like I needed a staff member to ask, “Is there anything I can help you find?” But I was too exhausted from travel and emotionally raw to approach someone myself, and unsure what question I would even ask. In the end I picked out this book and Thiese’s Notes on Complexity, all on my own.

I made some of my most vivid and satisfying reading memories carrying this around under my arm, sneaking pages whenever I could. On a trip to the publicly-owned lodging in Nikkou, maintained for residents of Tokyo’s Katsushika ward. At a tsukemen joint around the corner. At my in-laws’ creaky four-story house, about as old as me.

This volume deepens the sense of what it might really be like to become aware of one’s past lives, if such a thing were true. It successfully made me feel the gravity of waking up having witnessed your own entire lifespan in a medieval Europe or an ancient Egypt.

I’d worked my way through a couple of volumes of 惑星のさみだれ from the big Mizukami pile that my brother-in-law lent me, but set it aside for its unremitting shounenness. This series, he assured me, is more “spiritual”. So far I’m quite enjoying the admixture of the everyday modern Japanese setting and historically-inspired past societies.

Four years trying to get through this; the hardest volume for me, on account of how much of it is just military operations conveyed by close-ups of characters talking from inside GTM cockpits or vague “outside” locations, with minimal detail in the way of environments, objects, culture, or general sense of flavor. Every now and then you get to look at a GTM from the outside.

But even Nagano advises that folks skip ahead whenever they find they’re not enjoying an FSS story, and in the spirit of tadoku I finally took him up on it. I dashed through to the end and into Volume XV, already bringing me back to what I love about this series.

Favorites:

It may be my favorite Jessica McKenna fact that she of course always built Lego sets exactly according to the instructions and then left them in that perfectly constructed state. The childhood version of me who did that, displaying them all on a shelf, appreciates her for that. (It also seems significant that I later dumped all the Legos in a huge bin and invited the neighborhood over to create their own domains all across my room for a summer.)

Favorites:

KSR on Wolfe, including a detour through Proust!

What I mean is that after Wolfe read Proust, he understood he was free, free to become himself in any way he wanted, to become, like Proust, one of the great Modernist writers, all of whom make their own tradition, style, subject matter, and reality. After you’ve read a novel that contains a 240-page garden party, why should you fear anything? You can’t. Anything is possible.

A genius in Wolfe: and if there are any fellow postmodern materialists reading this and groaning at the idea of there being anything unusual inside an artist or anyone else, anything beyond the workings of the brain, I will agree immediately, but point out that the latest news from brain science makes it clearer and clearer that saying “only the brain” is not much of a delimiting statement. The brain is not a clockwork, nor a steam engine, nor a binary or digital computer, nor any of the machines we conceptualize it to be with our simple metaphors based on our own feeble handiwork, as if the brain could only be as complex as something we ourselves could make. Very much not the case. The brain is a kind of pocket universe. The mind is huge, and consciousness a small part of it. The unconscious may well be inhabited by “subroutines,” as the computer people would have it, processes that may actually be more like characters. Maybe they are like Jungian archetypes—a shadow seems likely, perhaps an anima or animus—but who knows. Very probably the brain consists of organizations even stranger and more various than that. It may be a kind of library of stories all telling themselves at once. And by way of stories written down, one unconscious mind communicates with other unconscious minds.

Favorites:

Notable for being Zroundbls’s early favorite during their induction into fandom. Also notable for having a surprisingly satisfying moral arc. Feels like part of a little golden age for Off Book, along with “The Center of the Bullseye”, “The Names of Our Family”, etc.

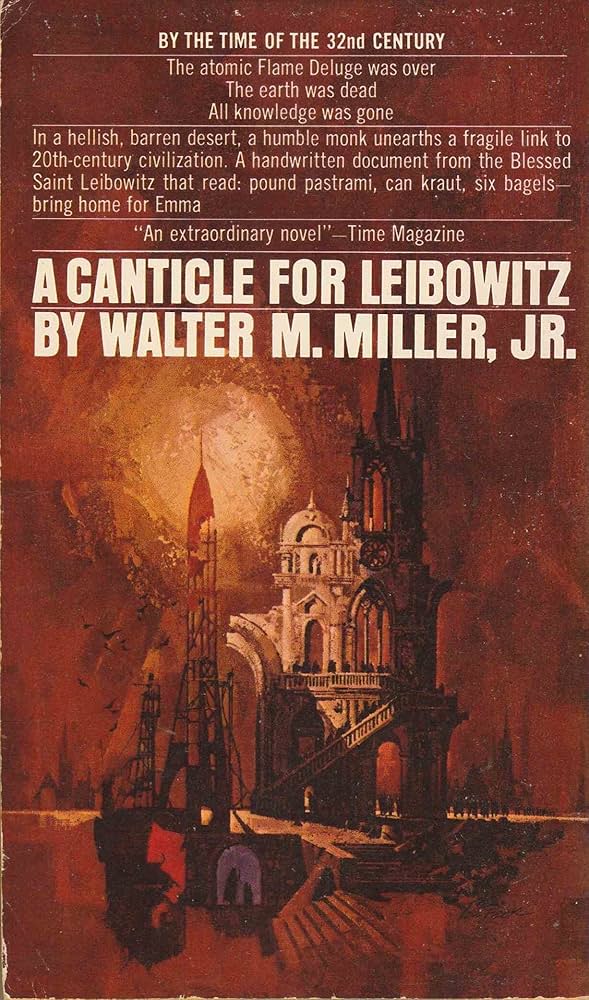

Late in high school I was sitting in the lobby of the administrative wing of my boys’ Catholic school. I cannot for the life of me remember what I was there for, but it has an equal chance of being because I was in big trouble for something, or because I was doing some sort of collaboration or meeting with someone important at the school. I was doing a reread of the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, perhaps in the big Bible-looking edition I was proud to have. Someone’s mom was coming out from the school office and she stopped in her tracks, striking up a conversation with me about books. She was impressed to see a student her son’s age reading one of her favorites. I have no idea whose mom she was. We connected easily and she made several recommendations, including A Canticle for Leibowitz and the work of Tom Robbins. I ended up reading several Robbins books soon after, but never got around to Canticle. (At some point I think I started confuse it with Flowers for Algernon.)

There’s apparently a copyright issue keeping the book off of the US Kindle store, but I found a SF Masterworks edition on the JP store and stripped the DRM.

ChatGPT looked at my reading list and, based on what it knows about me, acted surprised that I hadn’t read it yet.